The Life and Times of the Sicilian Robin Hood: Bandit and Murderer, or Hero and Patriot? — The Crime Library — Bandit and Murderer, or Hero and Patriot? — Crime Library

Introduction

“I live by my conscience and I do nothing anonymously. I am willing to take full responsibility in the eyes of God and man for all that I do. I have killed when it is just to do so, but never has Giuliano soiled his hands with blood for the sake of money.”

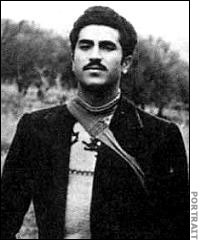

Salvatore Giuliano, 1946 (Quoted in Maxwell, G. Bandit. 1956)

A young man of twenty, handsome and fearless, was carrying two bags of grain from one Sicilian village to another. The state police, the caribineri, ordered him to stop. He was asked to produce his identity card. He gave it to one of the officers, who commanded him to release his bags of grain. The two argued. The young man protested that he was merely transporting food to the hungry people in his village, and the caribinere insisted that the young man reveal the source of his black-market grain. The young man felt threatened by the rifle that the frowning caribinere was pointing at him. He drew a Beretta from his waist and fired at the officer. Suddenly, the young man ran, leaving his identity card behind. He was fired upon by the other officer, and fell to the ground. The caribinere that he had shot was bleeding to death as the second officer fired again and hit the fleeing smuggler. The young man dragged himself into the scruffy vegetation. He was bleeding from a wound in his back. Because the caribineri had his identity card, it was not necessary for the officer to pursue the wounded culprit. It was another case of a black-market Sicilian peasant trying to avoid the authorities. He would either die like a dog in the underbrush, or find some other peasant to nurse his wound. They would find him soon enough.

Thus began the outlaw career of Salvatore Giuliano. Not only would he become the most famous fugitive in Sicily, but he would become a legend that fascinated most of the western world for the next seven years. A featured story with photographs appeared in Life. Articles about him appeared a half a dozen times in Time. Newspapers throughout Europe ran stories about his exploits almost daily.

Salvatore Giuliano, the Sicilian Robin Hood, had much in common with the legend of Sherwood Forest. Both were outlaws. Both reportedly stole from the rich and gave to the poor. Both practiced their craft in relatively small areas of some 200 square miles. And both were clearly legends.

But there is a difference. Robin Hood may or may not have existed. There is no doubt that Salvatore Giuliano existed. Rather than fanciful paintings, we have photographs of him. We have first-hand accounts of those who met him and knew him well.

Nonetheless, both Robin Hoods are legends in many senses of the word. Salvatore Giuliano not only became a legend in his own time, but the half-century since his death has embellished it, even as some writers have revised their estimate of him as nothing more than a common criminal. During his lifetime, women adored him, children prayed for him, fathers and mothers protected him, and young men joined him in the mountains above his home village of Montelepre. (It is not without irony that the home village of the elusive bandit is translated “Mountain of the Hare.”)

Who was this young man who became an outlaw at the age of twenty and was mysteriously killed at the age of 27? What did he do that made him world-famous while alive, and long remembered in his native land 56 years after his death? Was he indeed a hero, or was he nothing more than a bandit and a cold-blooded killer? To this day, historians are conflicted. He is either elaborated as a unique force in post-war Sicily, or dismissed as a mere outlaw, a common profession in the south of Italy.

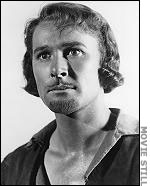

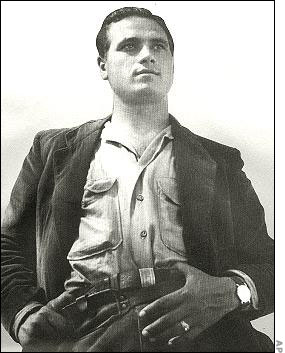

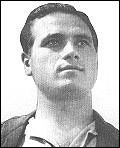

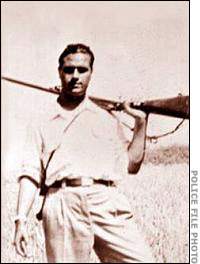

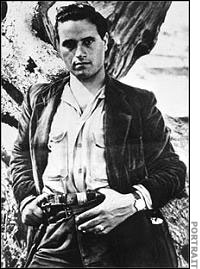

To look upon a photograph of Salvatore Giuliano is to look upon a young man of great physical beauty, of nobility, and of dark, cold eyes. His thumbs are hooked in his belt. He has an elaborate gold belt buckle and is wearing a large diamond ring and a gold wristwatch. His clothes are rough and serviceable, as if he were a hunter. He looks at the camera without emotion.

Most of all, he is defiant.

After that chance encounter with the killing of the state police officer in 1943, Salvatore Giuliano became a fugitive. He would be hunted relentlessly for the next seven years, defying the authorities to capture him. His legend began almost immediately after his wound had healed.

The identity card he had left behind gave the caribineri his name. Unfortunately for his father, Salvatore Giuliano, Sr., the authorities did not particularly care which Salvatore Giuliano they arrested. Giuliano’s father, uncle, and several cousins were imprisoned. Furious, Giuliano managed to free all but his father from the regional jail, an act so daring that it immediately captured the attention of the small towns west and south of Palermo. The lightly guarded jail was no match for the ferocity of Giuliano, as he literally shot his way into the building, wounded one guard, and subdued the cowering three others. Thus, with this audacious jail break, he no longer was a mere outlaw, but had now begun his career as a bandit. One of his closest friends, Gaspare Pissciotta, became his second in command. The core group of bandits probably numbered no greater than a dozen, though at times the government claimed that he had as many as a thousand men. (Later, when Giuliano took on more complex missions, he would augment his band with others, so that the group became as large as fifty. It was never much larger than that.)

The jail break was the first act to bring Giuliano notoriety. Soon thereafter he and his bandits attacked a caribineri barracks outside of Palermo, killing two of the officers and making off with a load of arms and ammunition. The mystique of Salvatore Giuliano was growing.

For the next three years Giuliano carried out a number raids, robberies, and killings. Some of the events surrounding these missions formed individual legends, the accuracy of which is difficult to determine. Some were probably true, some partly true, and some doubtlessly embroidered from a single, small incident. There are so many tales, however, that a great many of them probably happened.

The “Robin Hood” designation grew slowly from a number of small reported acts. Giuliano slipped money under the door of a sick old woman unable to pay for her medical treatment. He gave money to small children he found crying who had their money taken from them by the thuggish caribineri. He hijacked a truck of pasta and distributed it to hungry families in the village piazza. Whether true or not, the peasants in the villages around Montelepre marveled at these stories.

The most famous anecdote concerned his robbery of the Duchess of Pratemeno. According to accounts, Giuliano entered the sitting room of the duchess, addressed her courteously and formally, and proceeded to relieve her of her jewelry. The jewelry was produced, and, as Giuliano bent to kiss her hand, he noticed a diamond ring on her finger.

(The words of Giuliano in this anecdote are those reported by Maxwell.) “That, madam, is perhaps the finest of them all. May I have it, please?” She tearfully told Giuliano that it was a gift from her husband, a token of her first love. Giuliano removed it, purportedly saying, “Then I shall not sell it, but wear it myself. Knowing its history will make me value it the more.”

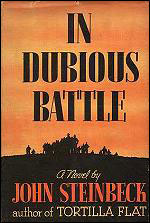

Giuliano noticed a book lying on the sofa. It was a translation of John Steinbeck’s In Dubious Battle. “I shall borrow this, but unlike the jewels, I shall return it,” he said. He returned the book a month later with a note:

“My dear Duchess,

I am returning herewith the book which I borrowed from you. I do not understand how a reactionary like you could possibly appreciate it, and I was tempted to keep it. But when Giuliano gives his word he does not break it.”

Giuliano

This story is obviously embellished, because the ring that was on Giuliano’s third finger (and appears in the famous Michael Stern photograph of him) was clearly larger than one the Duchess could have worn. Giuliano had kidnapped the Duke a year before, and it was then that he probably appropriated the ring. But Giuliano’s admirers found the story of the Duchess and the ring too romantic not to believe.

There were more than acts of kindness that contributed to the legend. The entire village of Montelepre supported Giuliano, and refused to provide information to the hundreds of caribineri who occupied the town. A few of its citizens dared to inform on him. One, a seventeen-year-old who joined Giuliano’s band on occasion, was caught listening at the door for scraps of information that he could sell to the local captain of police. Giuliano warned the boy that he was engaged in a risky business: “Never again to do anything so dangerous without my orders; you are a baby playing with the affairs of men.” A week later, the boy once more tried to pass information to the captain. Giuliano dragged the boy against a village wall and shot him.

Such executions of informers and traitors had an established ritual. The condemned was forced to say his prayers before being shot. After each execution, Giuliano pinned a note to the body of the traitor: “So Giuliano will deal with all those who spy against him.” Sometimes the note would be in the form of a poem.

In 1943, all of Europe was suffering. The effects of World War II were poverty, shortages, disorder, and a struggle for existence. The shortages were so severe that thievery and black marketeering became the general way of life for a significant percentage of European populations. Nowhere were the deprivations of the war and its aftermath more apparent than in Sicily. Even with the liberation of the island from the Nazis, conditions were very difficult.

By early 1946, Sicily was in one of its frequent states of political chaos, and Giuliano was well established as “The King of the Mountain.” These two apparently unrelated conditions soon merged.

The Fascists were gone. Italy was once more united, first under the king who had been deposed by Mussolini, then under a republican government based in Rome. As it had been for almost eighty years (since the unification of Italy into a single state in 1866) Sicily was both ignored and exploited by the central government.

Two thousand years of occupation by Greeks, Carthaginians, Romans, Arabs, Normans, Spanish, and French had created an island that was fiercely independent. This independence was more of an attitude than a reality, because Sicilians had been subjugated for so long by one conqueror or another most recently by their own central government in Rome.

A number of political parties came into existence. The most prominent were the Christian Democrats. One must understand that in Sicily, all political activity is intertwined with the existence of the mafia. Indeed, the coexistence of the Christian Democrats and the mafia bosses was a given.

The political situation in Sicily was further complicated by the existence of the latafondisti, the barons who had large expanses of land and who held their tenant farmers and part-time laborers in virtual slavery.

Giuliano inevitably became ensnared in politics. The relationship of banditry and politics was a long tradition in Sicily, with a prominent bandit emerging every seventy five to one hundred years. Each of these notables was linked to a political movement, mostly as a leader of rebellion. Many of these famous bandits (though none ever as famous as Giuliano) had their own armies. Agnello (1560s) had his own flag with a death’s head, and a fife and drum corps. LaPilosa (1647) controlled the villages surrounding Palermo and was linked to the greater underworld. Testalonga (1740s) exacted taxes from the peasants, in defiance of the Austrian rulers. During the Revolution of 1848-1849, the bandits Di Miceli and Scordato seized virtual power in their villages and marched their armies into Palermo. The move from sheer banditry to political power was a time-honored tradition that Giuliano followed.

By 1946, Sicily (and all of Italy) was in its time-honored tradition of political confusion. The left was represented by the Communists, the middle by the Christian Democrats, and the right by the Separatists, with smaller parties filling in the political spectrum. Indeed, there was even a surviving Monarchist party still seeking the return of the recently disposed king.

Two political goals motivated Giuliano. The first was to achieve enough political influence so that he could force a national government to grant him and his men pardons. The second was to have Sicily annexed to the United States as its 49th state.

From hijacking, robbery, and attacks on the caribineri, Giuliano branched out into another profitable activity: kidnapping.

This sort of kidnapping had nothing to do with the abduction of children for ransom. It was the capture of prominent adults who would be returned to their families for a sizeable amount of cash. In Giuliano’s case, he would never dream of abducting children, whom he held in high regard and affection. But a rich duke or prince was another matter.

The system followed certain rules. The target, known to be wealthy, would be kidnapped. The abductee’s family would be informed of the amount of the ransom required usually half of the suspected wealth of the individual and mafia representatives would act as “agents,” that is, they would convey the messages from the kidnappers to the families and collect the money. Naturally, the mafia took a percentage for its troubles. The amount of the ransom was negotiable, usually settling at a sum of several million lire. (The rate of exchange between the U.S. dollar and the Italian lira at that time was approximately 600 lire to the dollar. Hence, most of these transactions were around $50,000.)

The practice of kidnapping embellished Giuliano’s legend even more. First, he employed the Robin Hood tactic of robbing from the rich. Second, the accounts of his treatment of his captives reinforced his gentlemanly nature. A victim would be housed adequately, fed well, provided with books, and entertained by Giuliano. Reports after the release of the captives often spoke of how much they had enjoyed the experience.

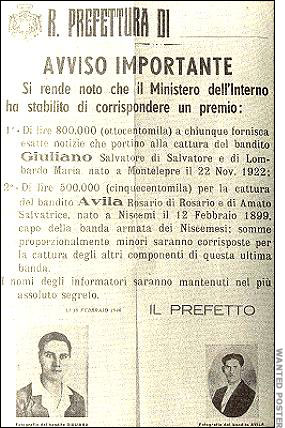

Sooner or later, a reward would be offered for the capture of Giuliano. The King of the Mountain would respond by doubling the reward for the death of the official who had proposed the reward. With the exception of a few brave souls, the rewards for Giuliano “dead or alive” were pointless, because informers were subject to Giuliano’s swift justice: a firing squad with a note pinned to the body.

[Translator’s summary of a letter to the President, dated 5/12/47. Name and address of writer: (Mr.) Salvatore Giuliano, Montelepre (Palermo) Sicily]

The writer is the present leader of an anti-Communist guerrilla group in Sicily and also the sponsor of an annexationist movement which advocates the separation of the Island of Sicily from the Italian Republic and its annexation to the United States. He states that the newspapers variously picture him either as a legendary hero or else as a common bandit. His only sin, he declares is the annihilation of Communism in Sicily and the admission of that Island as the 49th State of the American Union. He respectfully offers his services to the President for the achievement of both purposes and requests the Chief Executive’s moral support to that end. He also respectfully requests acknowledgement of the present communication.

(Harry S. Truman Library archives)

Giuliano packed so much into seven short years that it is easy to forget how young he was. At first glance, Giuliano’s letter to President Truman is, if not audacious, certainly presumptuous. But we must remember that we are considering a very young man of only twenty-five.

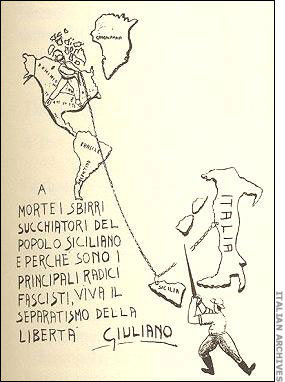

Such young men, particularly bold Sicilians, are idealistic. Giuliano was indeed bold, as well and charismatic and ruthless. But he was also, in his own mind, a patriot and a lover of giustizia (justice). Nothing would appeal to him more than the growing separatist movement, the separation of Sicily from the parasitic clutches of the central Italian government in Rome.

The Movement for the Annexation of Sicily to the American Confederation (MASCA) had been growing in one form or another almost from the establishment of the Italian Republic in 1946. MASCA was Giuliano’s contribution to the Separatist Movement, with himself as its leader. The mafia supported the idea of separation initially, as did much of the peasantry of western Sicily. While the MASCA did not gain seats in the National Parliament in the elections of 1946 and 1947, the Separatist Party was demonstrating strength in Palermo and the countryside west of it. If the mafia had not decided to throw in its lot with the Christian Democrats (whom they felt they could control and eventually did, right up to the prime minister), the movement might have grown into a formidable political party.

Despite the decline of the MASCA in particular and the Separatist Movement in general, and the victories of the Christian Democrats, Giuliano was undeterred. He created a famous poster which illustrated the severing of the chains that bound Sicily to Italy, with a cartoon of himself attaching the island to the United States.

The Italian Communist Party was showing surprising strength, particularly in the industrial north of Italy. Giuliano sent a second letter to Truman:

[Translator’s summary of communication, dated April 13, 1948. Addressed to the President. Name and address of writer: “Giuliano,” Montelepre, Sicily, Italy]

The writer is “Giuliano” (Note: a very famous Sicilian bandit chief, probably the most famous living criminal in Italy.) He offers his services to the President in connection with the inevitable war with Russia. He stresses that Russian agents have repeatedly contacted him with the aim of trying to enlist his support, but he tells the President that he is a firm believer in the principles of Democracy and will, until his dying day, fight for Peace, Liberty, and Justice. He makes it clear that, even if the President should find it impossible to permit him to support Untied States’ policy for international reasons, he will persevere in his anti-Communist efforts. The rest of his letter stresses the fact that he is an idealist at heart, and that while he has committed many crimes, he has not committed all that he has been accused of.

(Harry S. Truman archives)

Giuliano had altered his plea. The increase in appeal of the Communists throughout Italy and Sicily prompted greater concern for him than the issue of separation. He decided to support the party advocating the return of the monarchy, and declared war on the Sicilian Communists.

Actually, it was a war that he had been waging for over a year.

Throughout the first months of 1947, signs in enormous letters were painted on the walls of nearly every town and village in the Palermo region. They read: “Death to the Communists. Long Live Giuliano, Liberator of Sicily.”

Giuliano was an anti-communist not so much by an allegiance to political parties of the right, but more likely for his affinity for all things American, including the emergence of American opposition to the growing threat of the Soviet Union. It was, in effect, his response to the Cold War that was just beginning.

Surprisingly, the communists did very well in the elections of 1947, despite Giuliano’s well-advertised opposition. There is some evidence that Giuliano intended to either kidnap or assassinate the leader of the Sicilian Communist Party.

Sometime in late April, Giuliano received a letter, unread by others in his bandit band. After reading it, he gathered his band around him and declared that they were about to engage in an operation that would show the Communists that they had no future in the life of Sicilian politics. Even though the separatist movement was at a standstill, particularly since the mafia had withdrawn from the movement, Giuliano was still, at heart, a man who intended that Sicily should become a part of the United States.

The contents of the letter are not known. Giuliano destroyed the letter after reading it. Who was it from? Speculation is that it was from the Italian Minister of Security, with instructions to disrupt the May 1 celebration of the Communist Party. If that is true, then Giuliano was about to become a pawn in an operation that would, if not diminish his popularity, then seriously damage his credibility as the protector of the downtrodden.

In a vale between three villages Portella della Ginestra villagers gathered for a May-Day celebration of the recent Communist advances in Western Sicily. It was, as was usual on that day, a festive celebration of the Communist ideals. There would be banners and gaily colored carts and a parade and speeches by Communist dignitaries.

As the crowd gathered, as speeches were about to be made, shots rang out from the surrounding hills. Seventeen people were killed, and over thirty celebrants were wounded. Among the dead were children. It was an ambush of the innocents.

The aftermath of the massacre was condemnation of Giuliano, who later assumed responsibility for the slaughter. He maintained that the intention was to fire above the heads of the crowd, not to kill the innocent.

But the mysteries surrounding the massacre at Portella della Ginestra remain. Who sent the letter to Giuliano? What were its contents? Further, what was the role of the mafia in this unfortunate episode? Was Giuliano set up by either the federal government, or by the mafia, so that once and for all the King of the Mountain, the Sicilian Robin Hood, could be discredited? The testimony of some of those who were involved particularly Gaspare Pisciotta after Giuliano’s death, suggested that somehow the entire affair was not the work of the bandit gang, but of darker political forces.

The results were mixed. In the eyes of some, Giuliano was discredited, but others were convinced that the usually astute Giuliano had been deceived by some combination of mafia influences and federal government treachery.

Whatever the explanation, from this point forward, Giuliano had become a subject of controversy.

By late 1949, Giuliano was on the defensive. A few important members of his band had been killed or captured. A special task force had been established by the central Italian government to capture or kill him. This was a much more sophisticated group than the often hapless cariabineri, and it employed Giuliano’s own tactics to overcome him. Rather than large, immobile police forces, or small armies, the special task force broke into small bands of soldiers, imitating Giuliano’s methods.

As in all shrewd tactical maneuvers, informants became crucial to the enterprise. No one individual was closer to Giuliano, or more trusted, than Gaspare Pissicota. If the colonel leading the task force could convince Pisciotta to betray Giuliano, than their mission would be accomplished.

For a number of months, Giuliano had been urged to leave the country. Even a captain of the carbineri had urged him to flee to Tunis, from whence he could settle in the United States. By late 1949 and early 1950, Giuliano had decided that it was time to leave Sicily. He made plans. Some sixty miles south of his base in the mountains surrounding Montelepre was the town of Castelvetrano, almost on the south coast. There, from a small and insignificant air strip, Giuliano could be flown to safety.

Arrangements had to be made. Giuliano made several trips to Castelvetrano to prepare for his escape. He used as a base of planning and operations the house of a young lawyer.

It appears that Giuliano wished to leave with his trusted aide Pisciotta, and arrangements were made to meet at the lawyer’s house and depart for the air strip. On July 4, a weary Giuliano was waiting for Pisciotta. However, he had received disconcerting news from his captain friend. Pisciotta was prepared to betray him, having met with the leaders of the “get Giuliano” task force.

When Pisciotta arrived, Giuliano confronted him. They argued. Somehow, Pisciotta was able to convince Giuliano that he was loyal, that the report was false.

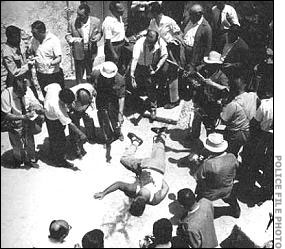

They went to sleep. According to Pisciotta’s confession at the trial held concerning the Portella della Ginestra massacre some months later, Pisciotta shot Giuliano while he was sleeping. He and the frightened lawyer dressed the body and dragged it out into the courtyard. The captain of the task force appeared, arranged the body so that a machine gun lay next to Giuliano’s body, and shot it several times. Shortly thereafter, the colonel of the task force appeared, and the two officials reported that Giuliano had been killed in a gun battle by the soldiers of the special task force.

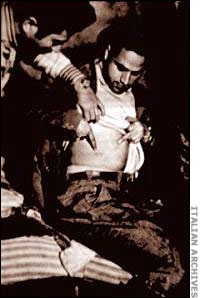

Soon, the courtyard swarmed with reporters and photographers. A photograph was taken of the dead Giuliano, face down, right arm spread out, dressed in slacks, a white shirt, and sandals, a machine gun a foot or so from his right hand.

The body of Salvatore Giuliano lay in the courtyard for some hours looked on by a crowd of Castelvetran citizens, many of them young boys from the neighborhood. His mother was brought from Montelepre to identify her son, now laid out, naked, on a slab in the morgue. The body was surrounded by blocks of ice, since the July days were typically hot.

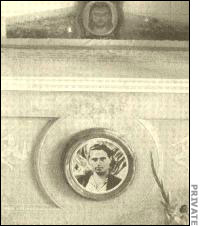

Two weeks passed. Daily, crowds would come into the morgue to view the naked body. Finally, on the afternoon of July 19, 1950, Giuliano was laid to rest in an above-ground crypt in the cemetery of Montelepre. There were no bells tolling. Those present were only seven family members and the police. All others were forbidden to attend. The simple marble slab said only “Salvatore Giuliano, 1922-1950.”

So, at the foot of the mountains that he ruled, the King of the Mountain was laid to rest.

Captain Antonio Perenze, second in command of the “get Giuliano” task force, gave the official account of the death of the Sicilian Robin Hood. The task force had trapped Giuliano in the lawyer’s house, he tried to shoot his way to freedom, and they had killed him in a fierce gun battle. Colonel Ugo Luca, several miles away from the action, waited for word from his deputy that the mission had been accomplished.

An astute reporter noted some strange inconsistencies in the official report. The blood that had seeped into the courtyard appeared fresh, although it had been two hours since the gun battle had taken place. They couldn’t find any witnesses who had heard the tumult of a prolonged gun battle. Indeed, two witnesses reported hearing only a brief report of machine gun fire.

Nonetheless, the report stood. Prime Minister Gasperi, in Rome, announced the immediate promotion of Colonel Luca to General.

Some months later, when the trial of the accused from the Portella della Genestra massacre was in progress in the mainland city of Viterbo, Pisciotta confessed that he had been the one who had shot Giuliano. A few days later, he testified that he had killed Giuliano on the orders of the Minister of the Interior, Mario Scelba, the creator of the Luca-Perenze task force. Scelba insisted that the official account was true, even after Captain Perenze recanted his initial description of the death of Giuliano.

It seemed clear to Italian journalists that an effort had been made to glorify the work of the task force, and, initially, to protect their informant, Pisciotta. The hapless Pisciotta had been promised much, and had even been given an official identity card in the months leading up to Giuliano’s death, so that he could travel to planning sessions with Colonel Luca and Captain Perenze. The significant meeting had been hosted by the mafia boss of Monreale. The desire of the government, whose involvement at various times with Giuliano, and their continuing corruption by Sicilian mafia, was, of course, to rid themselves of this popular and charismatic bandit. The mafia, as well, were finding that Giuliano was more than a nuisance, having defied them by killing four of their own.

Despite assurances to Pisciotta that he would be given amnesty for his services, he was sentenced to life imprisonment. He obviously knew much more than he had blurted out during the Viterbo trail, because he was poisoned while in prison in 1954, probably by the mafia, who had free entry into the prison. Despite his constant vigilance, Pisciotta drank his strychnine-laced coffee, unsuspecting that the mafia had achieved their goal of silencing him.

Strangest of all were the accounts that Giuliano had written a memoir, and that it contained damning information about the government. The young lawyer denied ever seeing this mysterious document, although there was testimony that he had burned it. He admitted burning some papers, but not a memoir. He said it had disappeared, and that he could say nothing further of it for fear of his life.

A draft of Giuliano’s autobiography was published a few years after his death, edited by his sister, Marianina. The memoir, however, was thought to be different, and it has long been assumed that it was a document that could do great damage to the central government and its partner, the mafia. If it is ever unearthed, then the story of Salvatore Giuliano would undoubtedly be even more astounding.

Coinciding with his rising prominence Portella della Ginestra notwithstanding Giuliano’s exploits became a fascination for the then most influential media, newspapers and magazines, and continued after his death.

In 1947, he was visited by an American journalist, Michael Stern, a dubious character who freelanced for American and European magazines. By wearing an American military uniform, he passed himself off as a quasi-official American government representative. The two most famous photographs of Giuliano were taken by Stern, and his article in the February 23, 1948 issue of Life made Giuliano a popular figure with many Americans. The article itself is mixed, attributing a much more criminal aspect to Giuliano’s bandits than they themselves felt.

A year later, the Swedish journalist, Maria Cyliakus, spent three days with Giuliano in the mountains. Her articles appeared in a number of European publications, and, unlike Stern’s treatment of the King of the Mountain, she was clearly an admirer. Her articles suggest that she was not only charmed by Giuliano, but smitten by him.

From time to time, Italian journalists were able to obtain interviews, and these reports, along with those of Stern and Cyliakus, produced two reactions. The first was that the authorities in Rome were infuriated by them. How is it, they asked, that journalists can find Giuliano but the carabinieri can’t? The second was the acceleration of Giuliano’s fame, so that his regional reputation of 1943 to 1945 became an enormous presence throughout Europe and the United States in the five years that followed.

After his death in 1950, there was an enthusiastic appraisal of Giuliano, the Robin Hood who had been betrayed by the man closest to him. Two films were produced. One, The Sicilian, based on the novel of the same name by Mario Puzo, portrays a sexy, swash-buckling, noble Giuliano. The second, Salvatore Giuliano, is considered a classic Italian neo-realist film, and was produced a mere ten years after Giuliano’s death. Its director, Francesco Rosi, presents Giuliano as a ghostly presence, showing him as a corpse or as a distant figure on a mountainside.

In recent years, historians writing about post-war Sicily have been less kind to the legend of Salvatore Giuliano, portraying him as just another Sicilian bandit, albeit one with a particular flair and panache. Two recent histories on the Sicilian mafia report that if Giuliano was not an actual, initiated member of the mafia, he worked with them. However, they acknowledge that his suggested mafia membership is difficult to confirm, particularly in the light of his spectacular assassination of four important Mafioso in 1949.

There is no question that Giuliano’s fame was a product of the media of the times. But it is also certain that his charisma, his good looks, and his boldness made him an inevitable subject for newspapers and magazines.

What are we to make of Giuliano?

Brigands and bandits were and are a continuing presence in Sicily. Why should we think that Giuliano was any different?

Part of the explanation can be found in the times in which he lived, and part of his fascination can be explained by a typical Sicilian state of mind. Times were harsh, government was in chaos, and heroes were few. Further, the centuries-old domination of the peasants in Sicily created a mind-set that resisted authority, however feebly, and glorified those brave enough to defy it on their behalf. Giuliano, at least in spirit, represented the defiance of oppression that the average peasant could not afford to embrace. This, in large part, explains why the citizens of Montelepre and surrounding villages went to such lengths to protect Giuliano.

However, there is no question that Giuliano was a killer. Admirers claim that he killed only when he had to, but the variety of his victims makes that claim suspect. His killing of informants was particularly cold-blooded, the messages pinned on his victims notwithstanding.

In order to understand him, it is necessary to consider the following: He was young. That fact is often forgotten. He had the idealism of youth, and with that the ability to rationalize his actions. He was charismatic, handsome, and, despite his youth, dignified, giving him an attractiveness not usually associated with a common bandit. He was, for a Sicilian peasant, articulate, and, in some ways, literate, so that he defied the usual image of thuggery associated with bandits.

And, most of all, he was in his way extremely patriotic. He seems to have genuinely believed in justice, the special identity of Sicily, and a simple interpretation of the American dream as it applied to Sicily. Indeed, in some ways, Giuliano considered himself an American. He was conceived in the United States during a period in which his family lived in New York. He was an admirer of President Truman and his determined stance against communism. He had planned to escape his pursuers by immigrating to the United States, where several members of his band had gone.

But legend surrounds him, and, as in the case of Robin Hood of Sherwood Forest, it is virtually impossible to capture him.

Only two biographies in English have been written about Salvatore Giuliano. The first, in a way pretending to be scholarly or authoritative, is by Gavin Maxwell. It has the advantage of having been written only a few years after Giuliano’s death, and the author had direct access to those who knew Giuliano. It is immensely interesting and has an immediacy about it that is arresting.

The second is a scholarly study written some thirty years later by a professional historian, Billy Jaynes Chandler. It is a complete and documented work, and it is particularly informative about the contexts of Giuliano’s life, death, and turbulent times.

Both books are important. The first is dramatic and laudatory. The second is impassionate and detailed.

The two principal interviews of Giuliano are quite different. The first, by Michael Stern, was obtained by deception. Stern is an ancestor of the sort of sensational journalism practiced by contemporary scandal sheets, and reports the apparently sensational without much verification of his conclusions. His article in Life was superficial, but his subject was so fundamentally impressive that even that (at the time) distinguished periodical could not dismiss Giuliano lightly.

Maria Cykalis was clearly smitten by her subject, and it is clear in her articles that she fell in love with Giuliano, not only with the man, but with his legend. She includes details that are almost tender in their description – the contents of Giuliano’s shaving kit, the description of him physically so that her affection for the man is palpable.

Other books, articles, and interviews about Giuliano in Italian have many important facts about Giuliano, but tend either to glamorize him (with some justification), or to assess him as a temporary historical phenomenon.

Giuliano is the hero of Mario Puzo’s novel, The Sicilian, a book that is entertaining and, for the most part, historically accurate. Giuliano’s personality, as imagined by Puzo, seems to be plausible. However, the film made from the novel is wildly improbable, with Giuliano appearing as a cross between Casanova and Billy the Kid.

Francesco Rosi’s film, Salvatore Giuliano, is a true work of art, although Giuliano appears only as a detached shadow. It recreates with great accuracy some of the events in the life of the bandit, including an impressive reenactment of the massacre at Portella della Ginestra which uses many of the people who were present on that fateful day. (As the scene was filmed, many of the “extras” fell to the ground in fear, believing that the massacre was once more taking place.)

All of this simply adds to his legend. Even revisionists, or those who write histories of post-war Italy and Sicily, are conflicted in how they try to assess Giuliano. Some barely mention him. That fact alone, that they felt it necessary to mention him at all, is significant.

BOOKS:

Barzini, Luigi. 1984 (originally published 1964). The Italians. Atheneum.

Casarrubea, G. 2001. Salvatore Giuliano. Milan.

Chandler, Billy Jaynes. 1988. King of the Mountain: The Life and Death of Giuliano the Bandit. Northern Illinois University Press.

Dickie, John. 2004. Cosa Nostra: A History of the Sicilian Mafia. Palgrave/Macmillan.

Di Scala, Spencer M. 1995. Italy: From Revolution to Republic, 1700 to the Present. Westview Press.

Finley, M.I., Denis Mack Smith, and Christopher Duggan. 1987. A History of Sicily. Viking.

Maxwell, Gavin. 1956. Bandit. Harper.

Puzo, Mario. 1984. The Sicilian. Ballantine.

Randa, F. 2002. Salvatore Giuliano. Palermo.

Stille, Alexander. 1995. Excellent Cadavers. Vintage.

MAGAZINES:

Stern, Michael. 1948. King of the Bandits. Life Magazine, February 23, 1948.

FILMS:

The Sicilian. Artisan Films, directed by Michael Cimino, 1987.

Salvatore Giuliano. Janus Films, directed by Francesco Rosi, 1961.

DOCUMENTS:

June 16, 1947. Document referred to the Department of State, Harry S. Truman Library, Independence, Mo.

July 1, 1947. As above.